Features

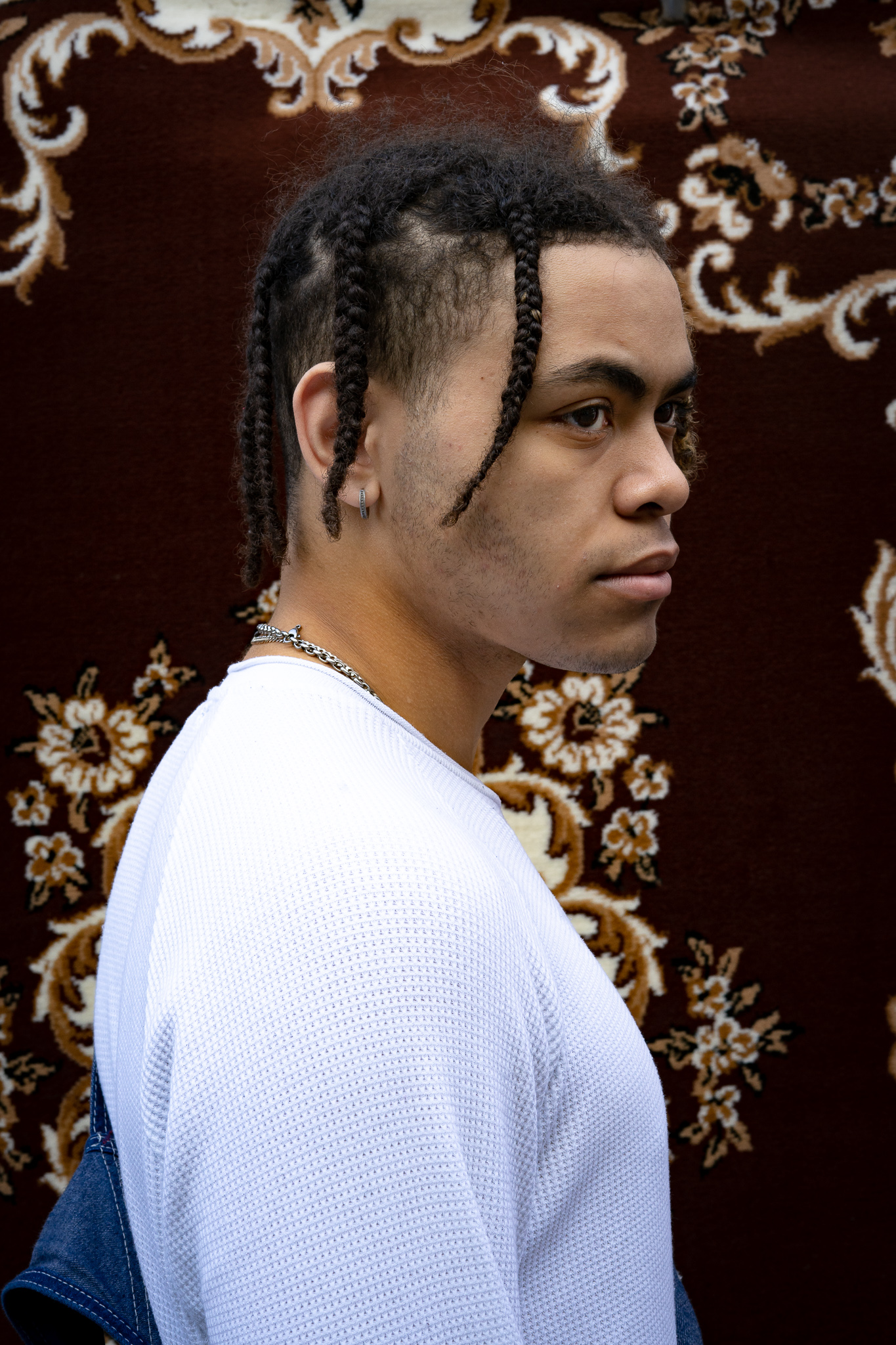

Amin McDonald Captures Masculinity With Portrait Photography

By Ellen Clipson - 3 min read

Read our Q&A session with London-based film and portrait photographer Amin McDonald about capturing visual stories that focus on critical narratives shaping youth culture and gender identities.

As winner of our British Culture Mission, Amin McDonald’s portrait photography captures the intricate and deeply personal elements that contribute to modern culture today.

Born in Jamaica and brought up in London, Amin was exposed to diverse communities from a young age. Using his background of Fine Art, Amin has become committed to telling unique stories of the unique individuals that built his ever-changing surroundings.

We caught up with Amin to discuss his recent project ‘They Who Laughed.’ A thought-provoking film photography project that presents a refreshing narrative to the concept of ‘masculinity’ in the 21st Century.

Evoking Honest Conversations About Gender Expression and Identities

How did you start out in photography?

It started in school. I was studying Fine Art in the UK, which gives you the opportunity to explore different mediums in the Arts such as graphic design and photography. I was open-minded. I wanted to use something that could be sustainable because trying to make it as a painter is near impossible without finances and support. So I bought a Samsung NX3000 for about £300 at the time and then went out on my own to shoot.

I still believe that Samsung should make more cameras, the quality on that little bug was fantastic. Joining Instagram (when it was still fresh) gave me confidence and I decided to shoot portraits of people on the street. It was a rush and everything went from there.

“Photography gives you the power to speak a thousand words with light, speed and colour”

For you what is the most important thing that photography can do?

Photography has great power. For those who are trying to make a difference, photography is here to enforce. Similar to how paintings were carefully crafted to create beautiful and intricate stories, photography does the same.

Photography gives you the power to speak a thousand words with light, speed and colour (or absence of it). Telling your own story that matters to the world or being part of a revolution, framing what is in your best interest.

I believe that you should never forget about your power to tell a story because of the presence and story that you have could make a difference to anybody in the world.

“People have realised the psychological value of being able to express emotions freely”

What is your relationship with your subjects?

Most of my subjects, I’ve never met before. My subjects usually come through friends of friends, so there’s already this mutuality involved that makes us a bit more comfortable with each other. There’s also something about using people who generally don’t model. Their down-to-earth attitude is something that attracts for my projects.

How does this affect your photography?

The discomfort when there’s no connection is definitely prevalent in the work and so I like to keep this comfort throughout my work. It’s my role to become their best friend, even for the day. You create a connection and relationship that hopefully will last longer than one shoot.

Is this project ongoing and how will you know when it should come to a close?

The theme is ongoing but the project itself is over. I guess there’ll always be many stories regarding masculinity. Experiences through life will be the driving force for many projects, for many people, and perspectives on modern masculinity are diverse.

I wanted to represent what I know. I realized that youth are idolising a representation of a male with toxic standards. I saw it in my 8-year-old brother who felt that it was better to not talk about his pain in fear that he’d appear weak. I really wanted to symbolise my own experiences as a boy and adulthood and what it felt like in-between the two.

How would you characterise modern masculinity?

The idea that you’re being a bit more aware of your own emotions and not suppressing it to critical states is what I believe constitutes as part of modern masculinity.

People have realised the psychological value of being able to express emotions freely and also supporting one another in that state. Traditional masculinity carried an image with itself. This image eventually became toxic.

Masculinity as a term is being redefined because a lot of people don’t feel like they’re being included. The world is shifting and changing and what makes somebody masculine, isn’t the same as it was thirty years ago.

What did you use to shoot this project?

I kept the project simple. In order to communicate a more emotional message, I use Portra 400 in an Olympus OM2 with a 28mm. Then for clearer, intimate portraits, I used my a7II with a 50mm prime.

What’s your best advice for photographers starting out?

I actually have a few things to say here. Firstly, make sure you love what you’re doing. Even when you haven’t earned a penny, be happy to create something. Before I got into photography, I was into literacy and creating stories. Now I’m putting that into imagery. If there’s a drive behind your work, it will show.

I would also say aim to be the best at what you’re doing by learning to express yourself. Take your time and refine your style.

Lastly, read because the best of us are the ones that read the most. Be inspired by everything around you, it’s all here for a reason.

Feeling inspired to share your own visual stories? Submit your photos to The 2019 EyeEm Award’s 10 categories to have your work globally exhibited, win new cameras and a trip to Berlin! Enter here.