Features

Chaos Is My Paintbrush: Thiago Dezan on The Dangerous Reality of Documentary Photography

By Ellen Clipson, and Eva Karl - 4 min read

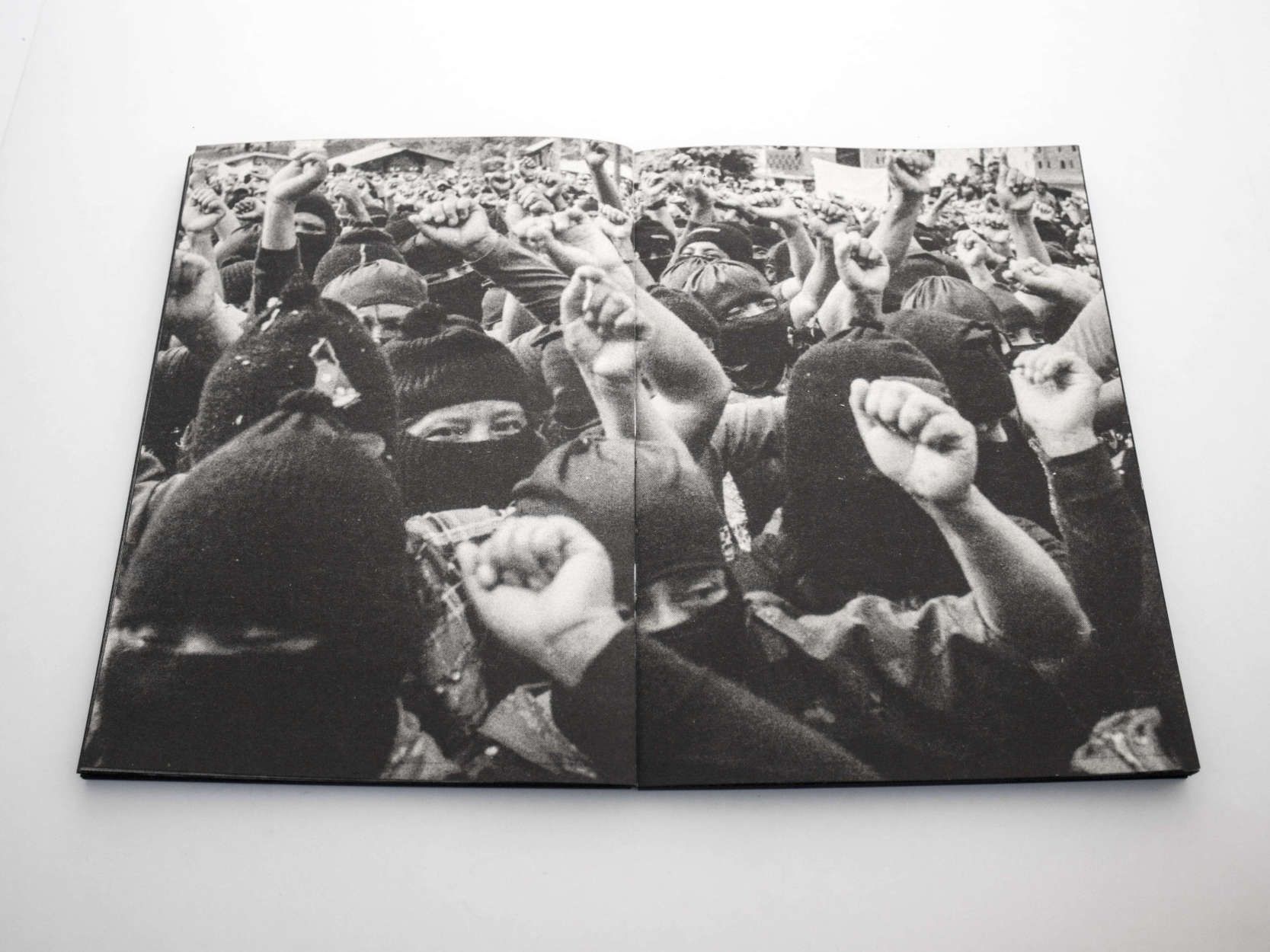

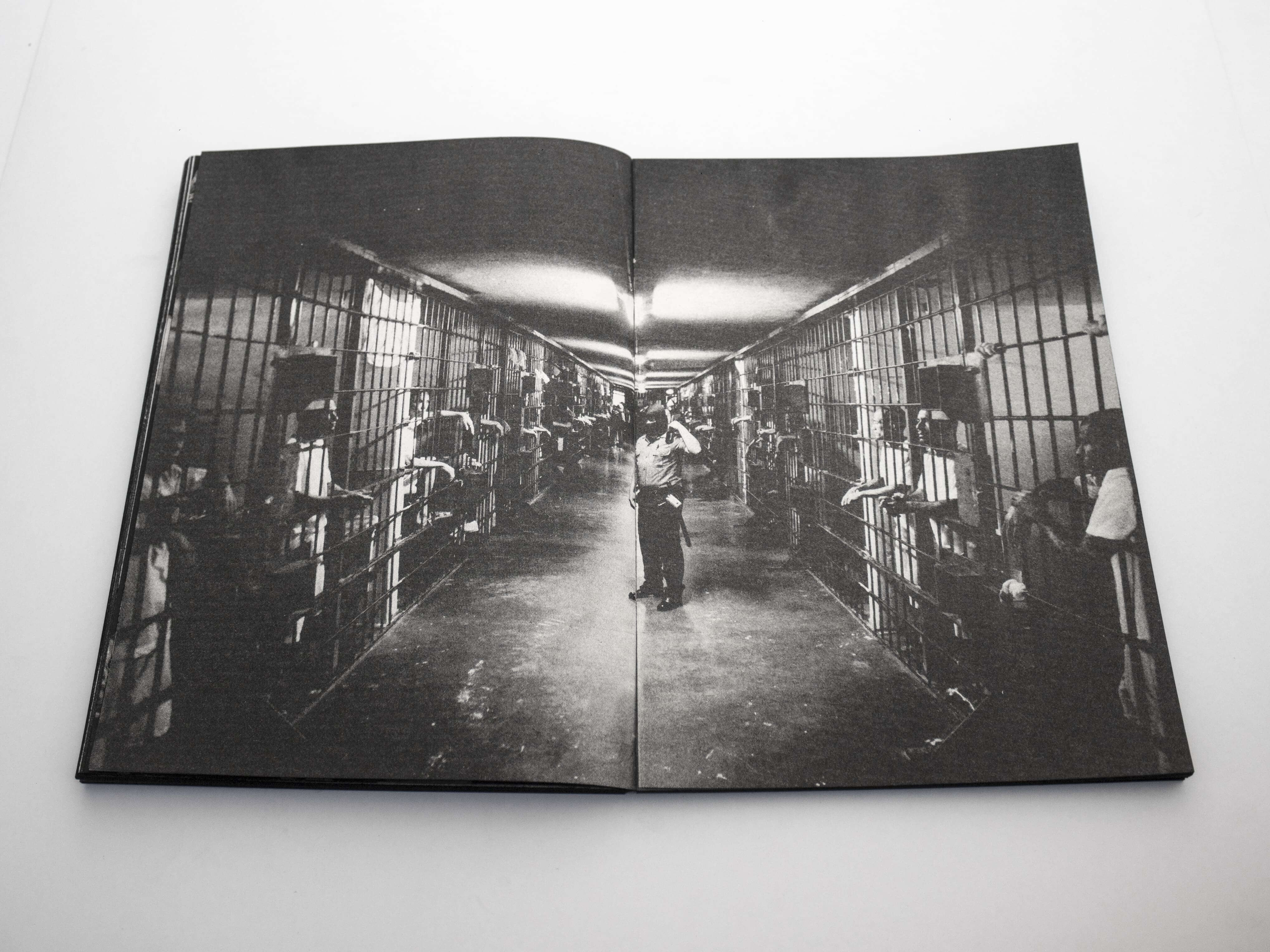

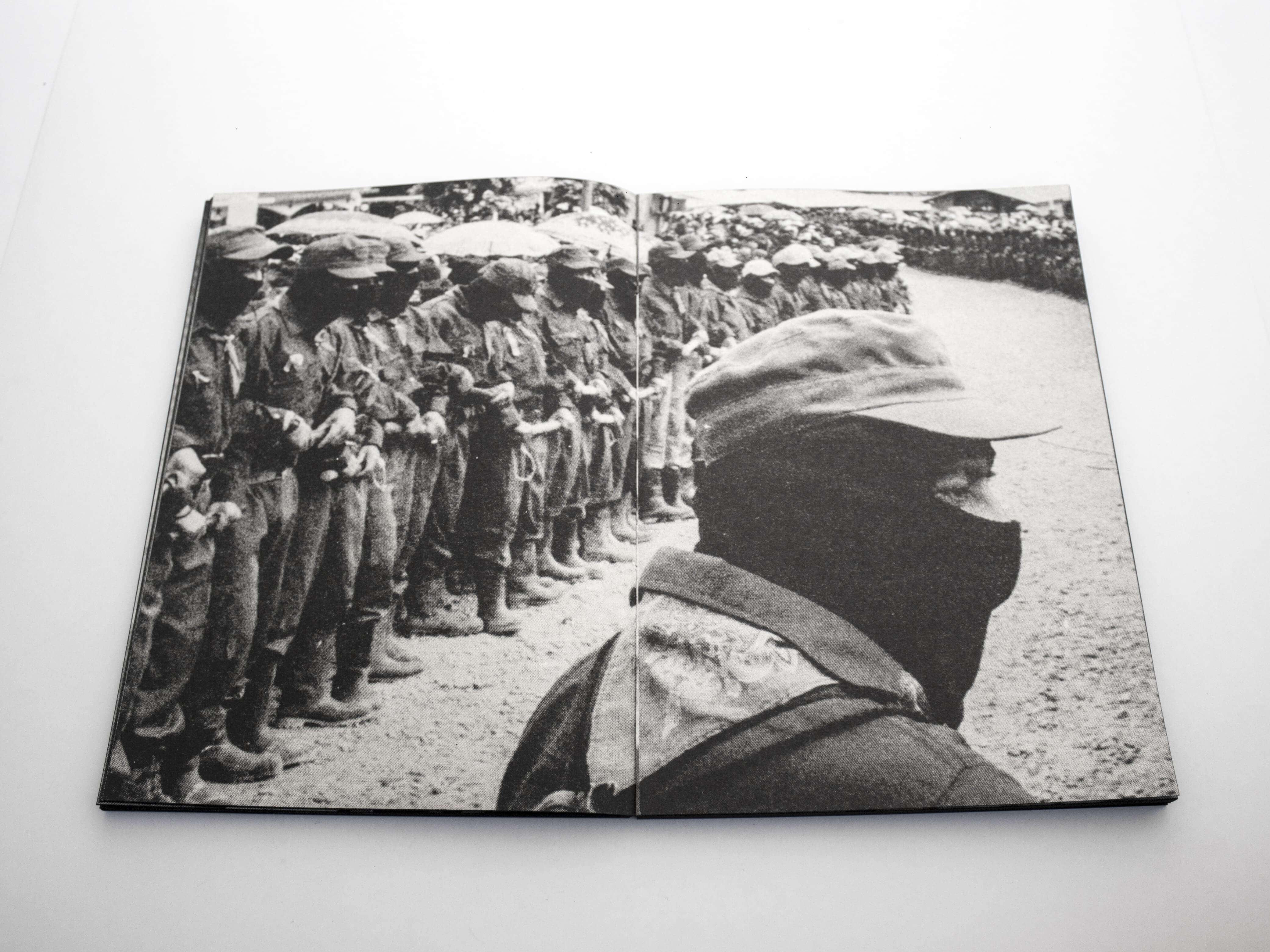

From protests that changed history to the world’s most dangerous prisons, Thiago Dezan tells us more about the real cost of being a documentary producer on the front line and why he made the decision to release his very first book.

Having started at the age of 16, Thiago Dezan produced his first video in Cuiaba, Brazil. Since then his filmmaking and photography has taken him around the Americas and led him to start NINJA, an independent network that covered some of the most significant protests in the region’s history.

Driven by a deep empathy born out of his years seeing and hearing personal accounts, his work seeks to tie together various stories and contexts to uncover the deeply embedded narratives of suffering, despair, and resilience that continue to shape the region. We spoke to Thiago about the reality of documenting hard-hitting stories.

Visualizing Stories of Despair, Hope, and Resilience

Congratulations for the launch of your recent book–When I Hear That Trumpet Sound. How long have you been working on this project and where was it shot?

The first images of the project are from 2016. Since then I have visited 16 countries around the Americas. Although not everywhere made it to the book, it helped me to have a better understanding and a deeper connection with the region.

The project evokes a rare conceptual density, positioned within a broad narrative that spans from religion to protests and prisons. Is there a core theme that you want your audience to consider when seeing your work?

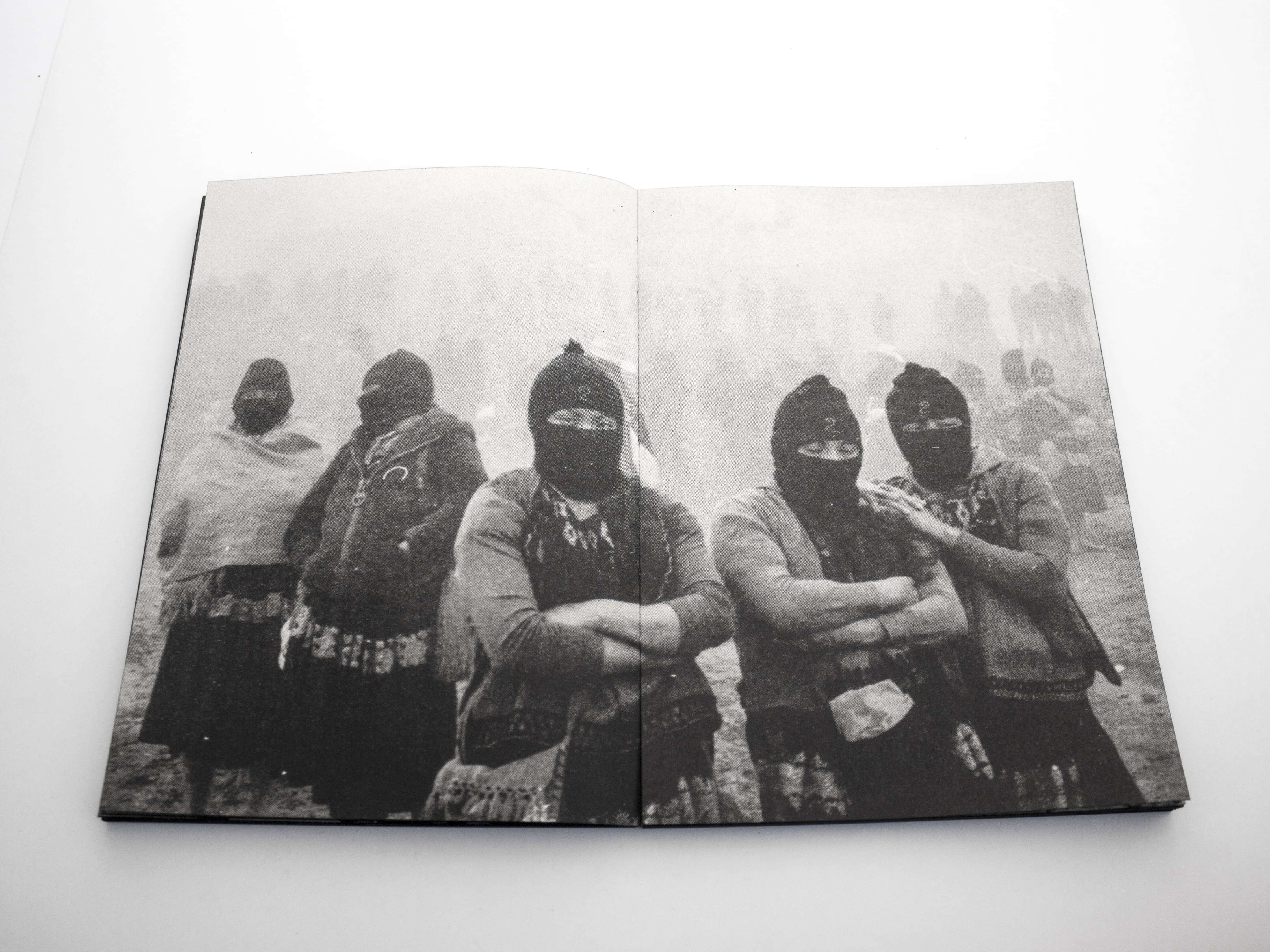

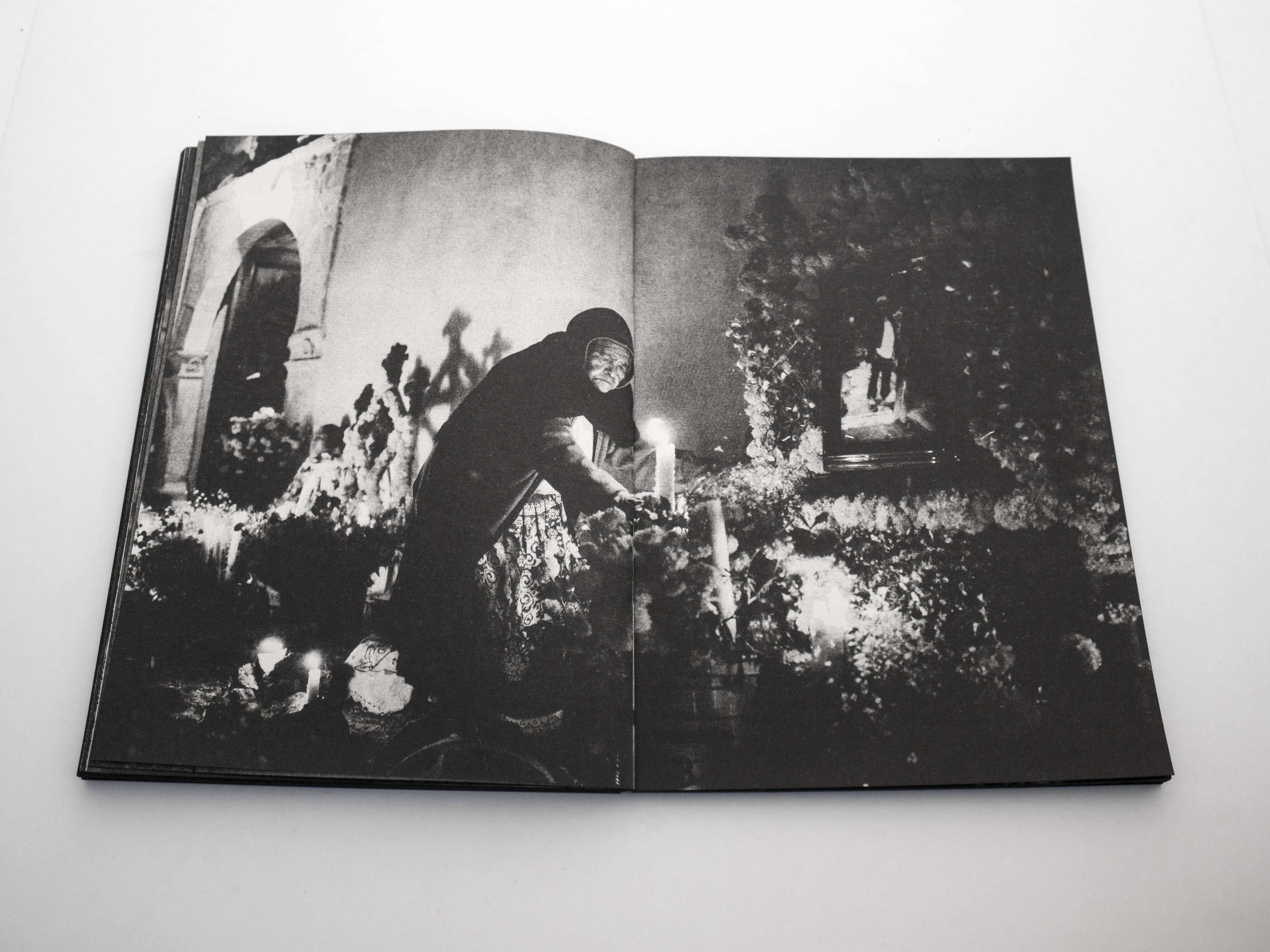

The book is inspired by the song ‘Ain’t no Grave’, written by Brother Claude Ely and immortalized by Johnny Cash’s voice. The song narrates the biblical moment when the last trumpet sounds, all the dead are raised and we all are changed. In the book I use this as a metaphor to verse about resilience and the powerful will people in the Americas have.

Was there a beginning and end to this project or did it become something more concrete throughout the documentation process?

I always had the idea for this project in the back of my mind, so everywhere I went I photographed taking the concept of the book into consideration. At the beginning it was very hard but after inviting Vitor Casemiro and Gui Galembeck to help me edit the story became much more clear. We were able to come up with the deep narrative of struggle and resilience in honor of the people that insist on surviving despite how oppressed they are.

What was your main motivation for bringing this particular project to print?

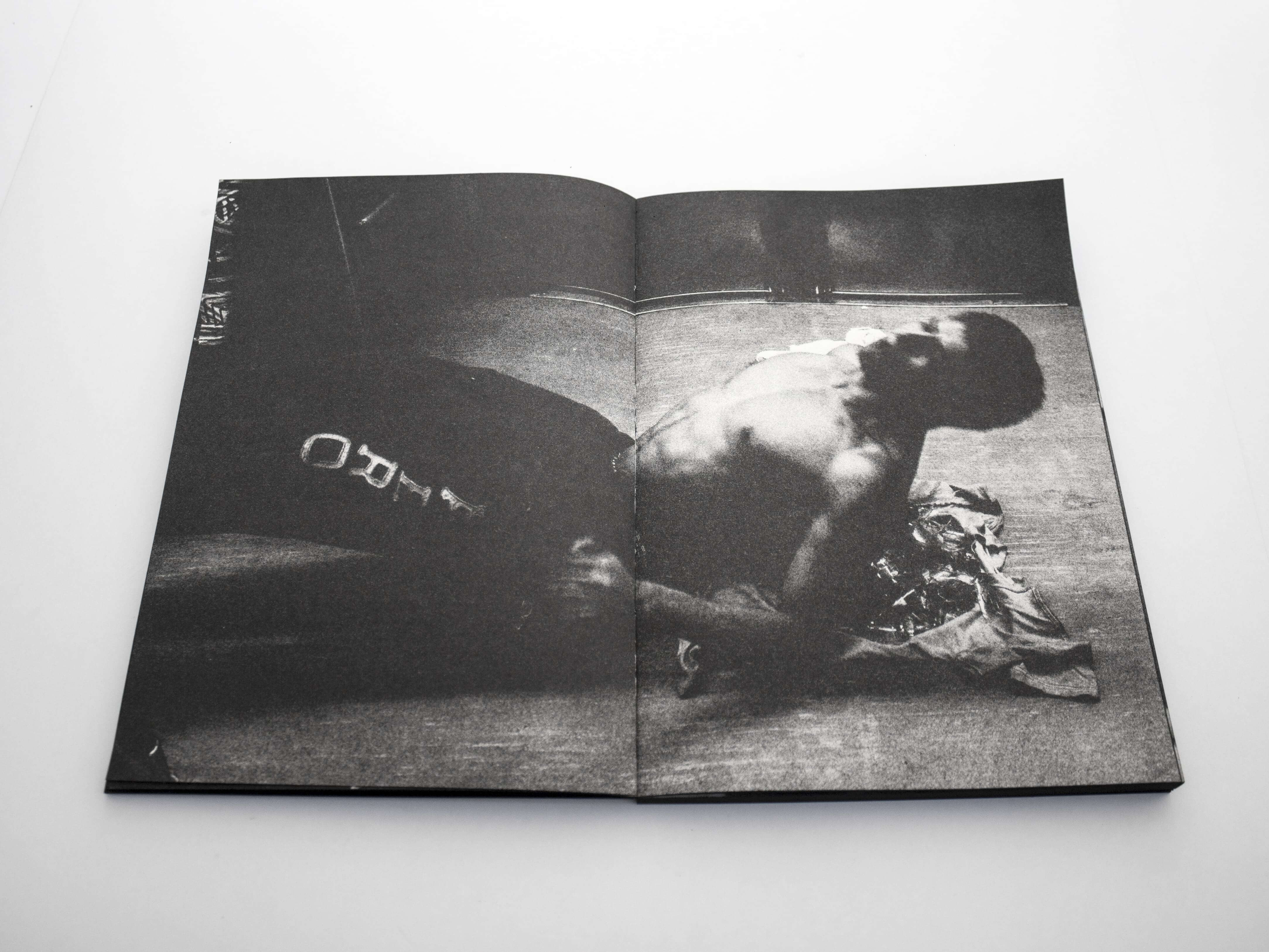

I tried to create a sensorial narrative that depicted not only one character or story but tied together various stories and contexts. In this way the photos should take the viewer through a wider narrative of humanity in the Americas and how we suffer from similar issues no matter which country we are. I tried to leave room for wonder and for the reader to question without me giving all the answers straight away. The book has the ability to be less direct and more experimental than something like a news article or documentary.

Can you describe the process of creating a photography book?

It was difficult to carve out the first draft of the book because there was so much content and everything looked essential to begin with. However, after making the initial dummy version the path for the story opened itself up and the editors, Casemiro and Galembeck together with the designer Bianca Buteikis, and I decided to follow the lead that the book was giving us.

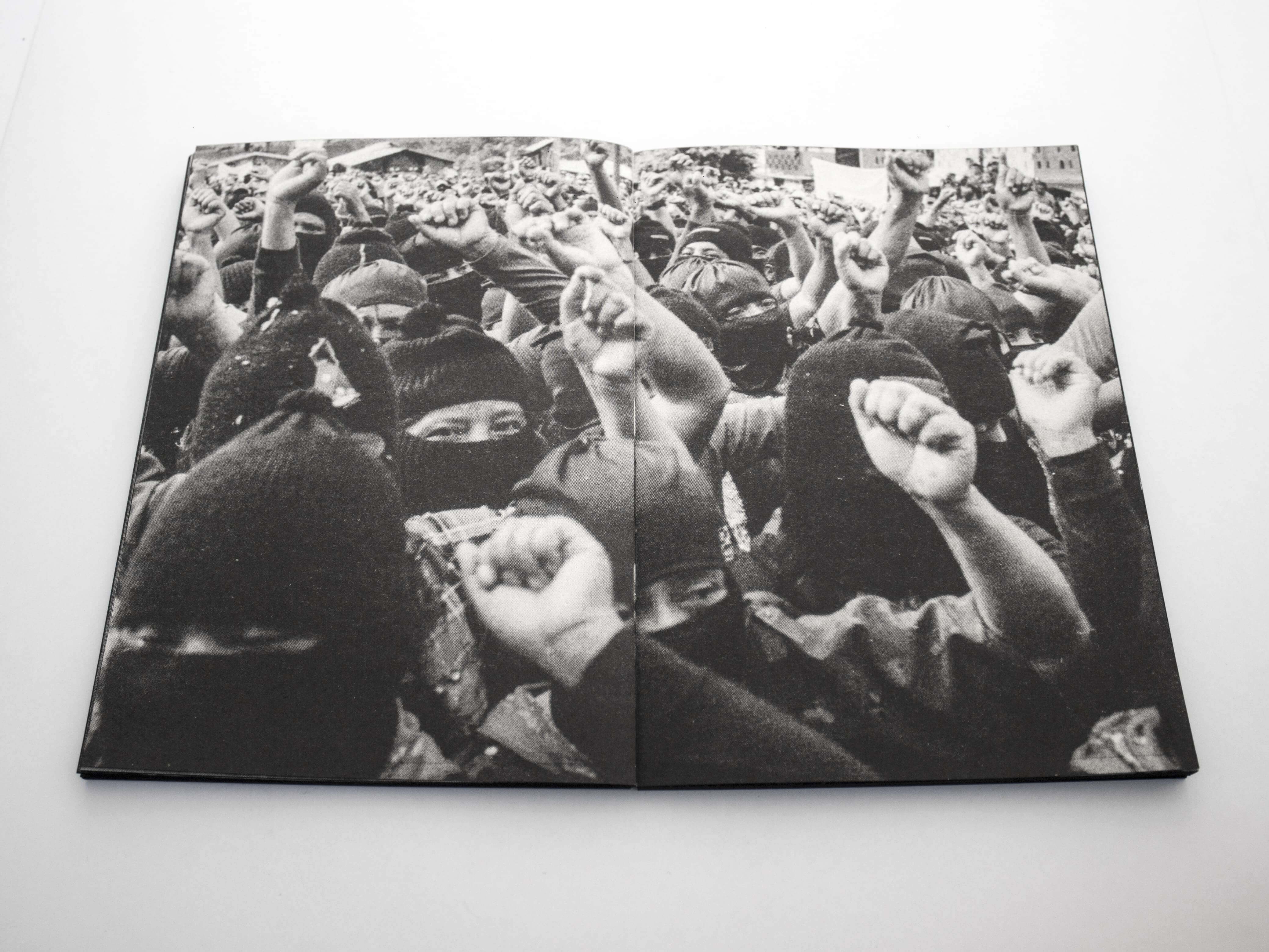

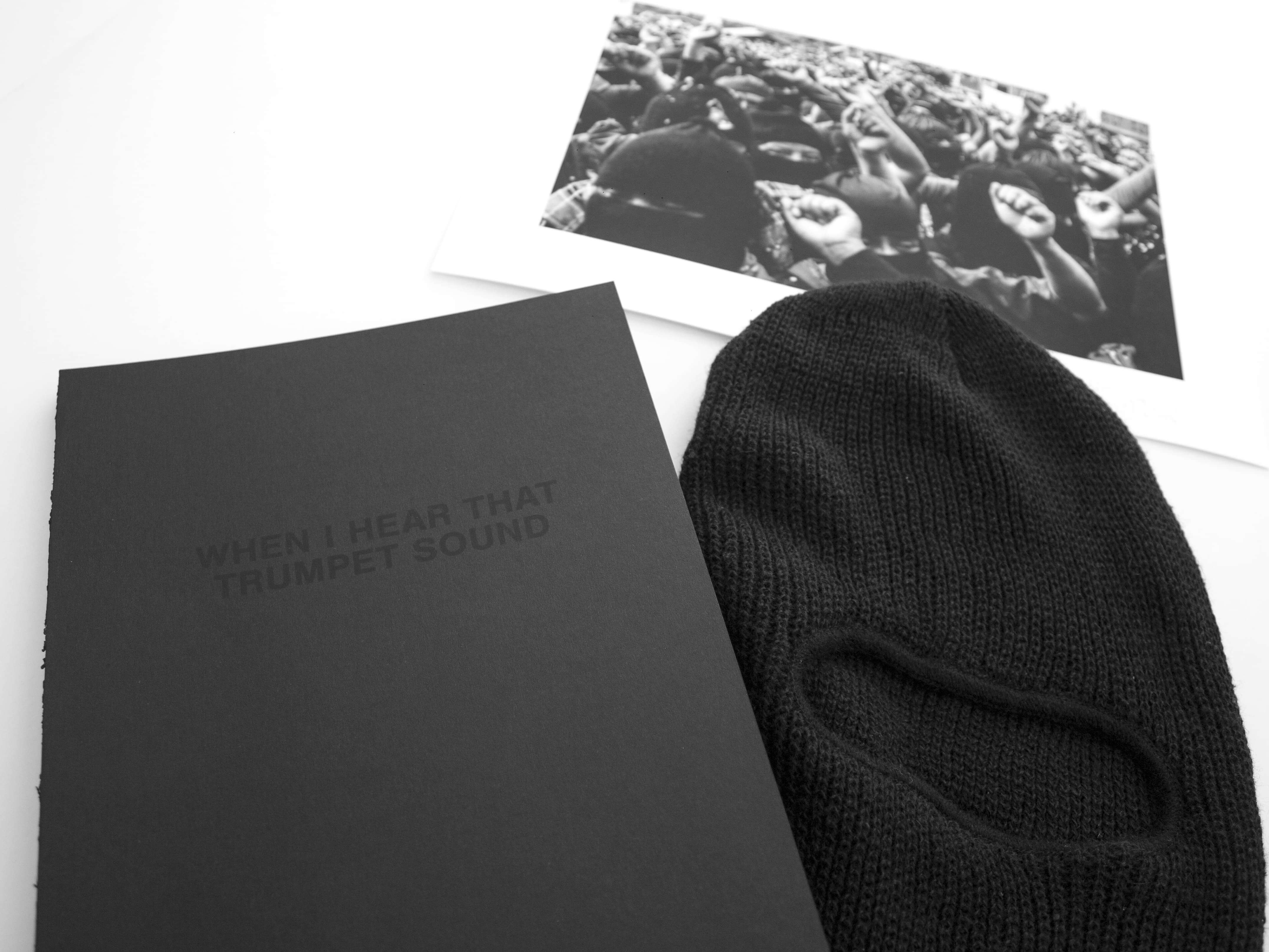

The photos were dark, noisy, and grainy. So we decided to go for risograph printing which adds another layer of texture to the photos. The book is about life, death, and struggle, and so we decided to have a black cover and paint the edges of the book with black ink. The story itself is more important than the title, so it is written on the cover in a way you can barely see it. Everything has a purpose in this book and I’m very thankful for having good people working with me to make it become real.

Purchase your copy of ‘When I Hear That Trumpet Sound’ here.

“It has no staged images, they are all snaps of life that together compose a melody of what it is like to have the Americas under your feet.”

You’re not only a photographer, but you are also a filmmaker. How do you balance the two roles when documenting?

I started making videos with tape cameras when I was 16 years old. It quickly took over my life and became my profession and passion. Photography came later. This was good because I already knew how to express myself visually and so it was another creative tool to use when ready.

I realized early on that, through videos and photos, I could say what I wanted to put out to the world and also spread stories and situations that intrigued me. This makes you meet many people, learn of many tragedies, and hear how people grow over it. All of this enriches you as a human being and teaches you to respect the people or communities that you are portraying.

Watch the short film trailer for ‘When I Hear The Trumpet Sound’ here.

“In an artistic sense, chaos is my brush.”

To what extent is documentary photography a reflection of reality or an act of resilience and opposition?

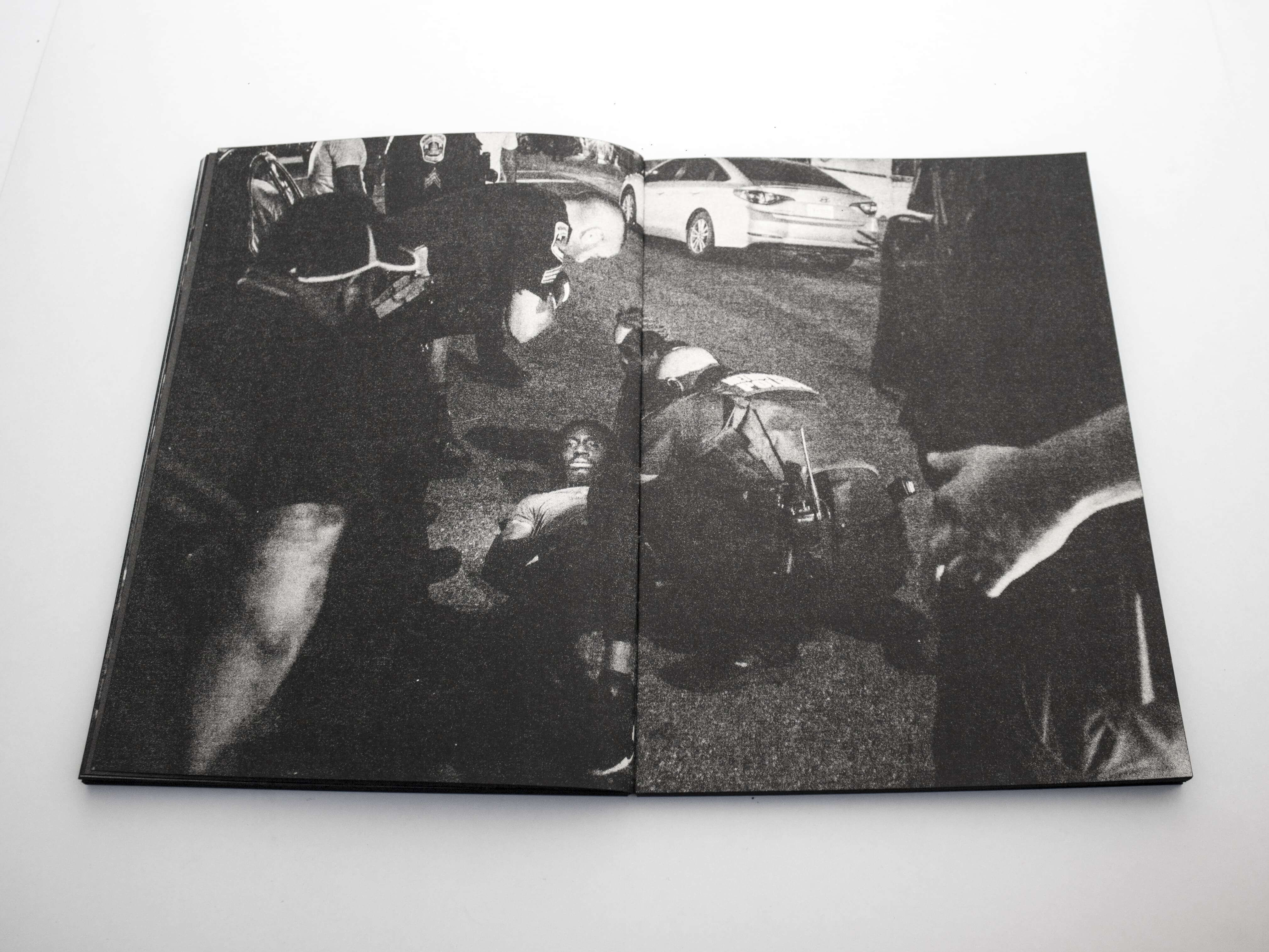

While editing the editor and I used to say that the book should be a chant of resistance. That is also the reason we chose to make a book out of this project. We felt more creative freedom to tell the story from a personal perspective and leaving gaps to be filled by the reader. The book is documentary in the sense that it has no staged images, they are all snaps of life that together compose a melody of what it is like to have the Americas under your feet.

The quote “I photograph to not feel bad, I feel bad for what I photograph.” is extremely powerful. When it comes to your documentary work, would you say your are more motivated by a personal sense of hope for the future or current despair?

In an artistic sense, chaos is my brush. The current despair is what motivates me to go further, searching for stories and for interesting people. I want more people to help me make sense of the world I see. The result of what I do with this ‘chaos brush’ is a painting of hope. Not a naive meaning of hope in someone or something higher, it is a hope in people, in ourselves, and our strength to overcome the barriers in front of us.

“The key to compelling storytelling is empathy.”

What does it really feel like photographing and filming in the midst of protests or documenting the inside some of the world’s most ‘dangerous’ prisons?

To be honest sometimes it gets quite heavy on one’s mind. I think the key to compelling storytelling is empathy. If you can’t place yourself in someone else’s shoes you won’t be able to capture the essence of a situation, making it impossible to report in a way that will honor the people who shared it with you.

To do that you need to immerse yourself, to fully comprehend and to be accepted so that you can understand the pain and try to find a way to translate it into images.

Do you have any advice for anyone starting out in documentary photography or photojournalism?

It is very important to study the ones that came before us. Do a lot of research and see a lot of good work. The only way (that I know at least) to find your own voice is practicing exhaustively and having solid references or inspirations to guide your praxis.

Get your own copy of ‘When I Hear That Trumpet Sound’ on Thiago’ website.

Follow him on Instagram, and Vimeo to stay up to date with his latest work.